The dowel joint

Master wood scientist Bruce Hoadley explains why round tenons fall out of round holes—and offers a workaround compromise.

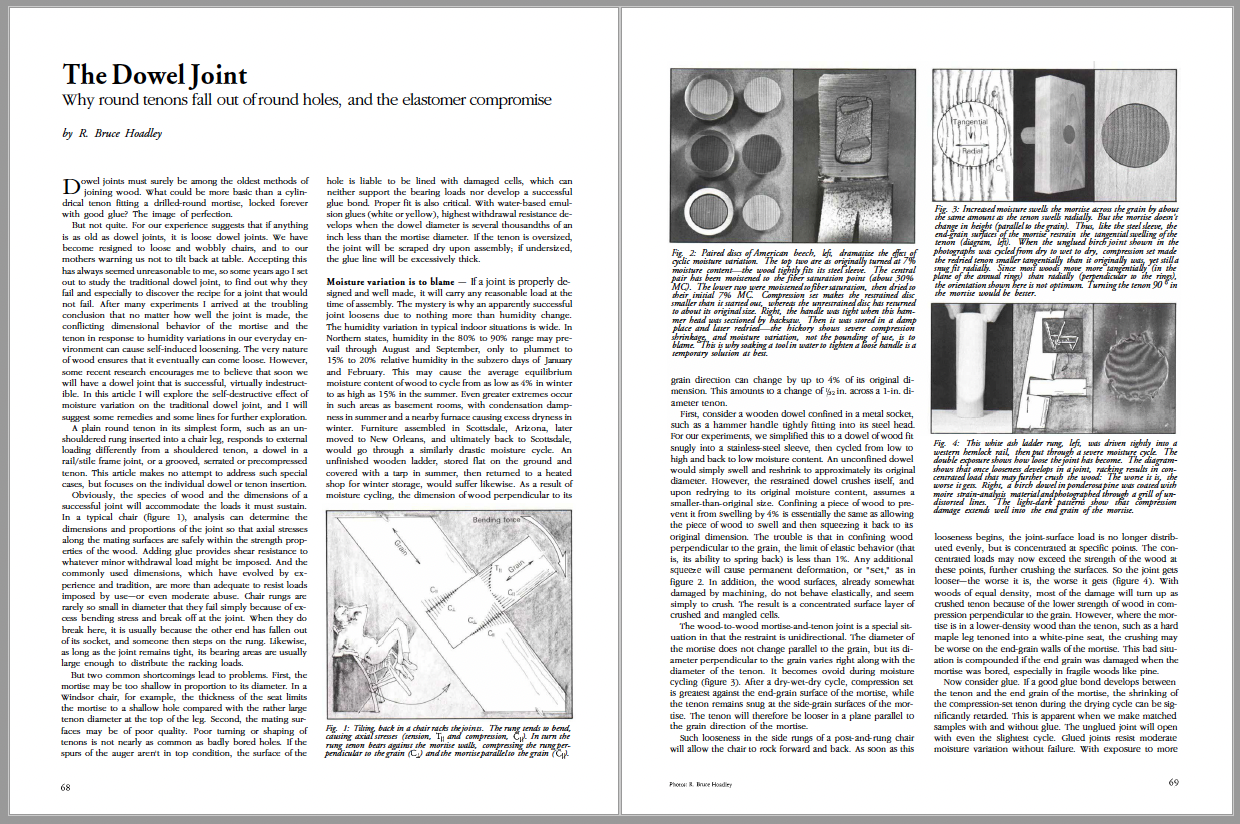

Synopsis: If good dowel joints aren’t the oldest joints ever made, loose ones must be, writes R. Bruce Hoadley. He studied dowel joints to find out why they fail and to discover the recipe for a joint that wood not fail. He found that conflicting dimensional behavior of the mortise and the tenon in response to humidity change can cause self-induced loosening. In this detailed article, he explains the self-destructive effect of moisture variation on the traditional dowel joint and suggests remedies and lines for further exploration. He establishes five checkpoints for making joints with the best chance of survival: proportions, original moisture content, mortise surface quality, grain/growth-ring orientation, and finishes. He covers adhesives and plenty of drawings illustrate various points. Side information talks about another solution from John D. Alexander, Jr., using green wood.

Dowel joints must surely be among the oldest methods of joining wood. What could be more basic than a cylindrical tenon fitting a drilled-round mortise, locked forever with good glue? The image of perfection.

But not quite. For our experience suggests that if anything is as old as dowel joints, it is loose dowel joints. We have become resigned to loose and wobbly chairs, and to our mothers warning us not to tilt back at table. Accepting this has always seemed unreasonable to me, so some years ago I set out to study the traditional dowel joint, to find out why they fail and especially to discover the recipe for a joint that would not fail. After many experiments I arrived at the troubling conclusion that no matter how well the joint is made, the conflicting dimensional behavior of the mortise and the tenon in response to humidity variations in our everyday environment can cause self-induced loosening. The very nature of wood ensures that it eventually can come loose. However, some recent research encourages me to believe that soon we will have a dowel joint that is successful, virtually indestructible. In this article I will explore the self-destructive effect of moisture variation on the traditional dowel joint, and I will suggest some remedies and some lines for further exploration.

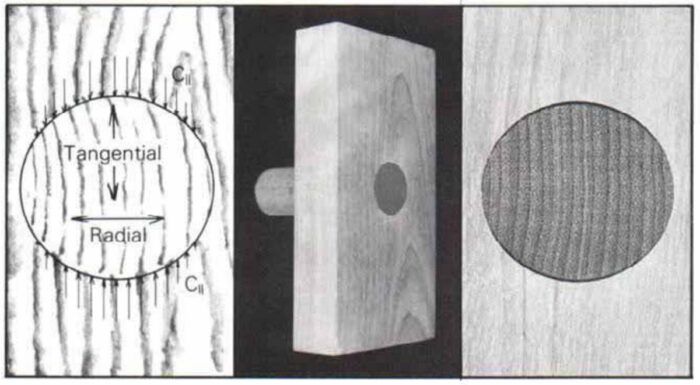

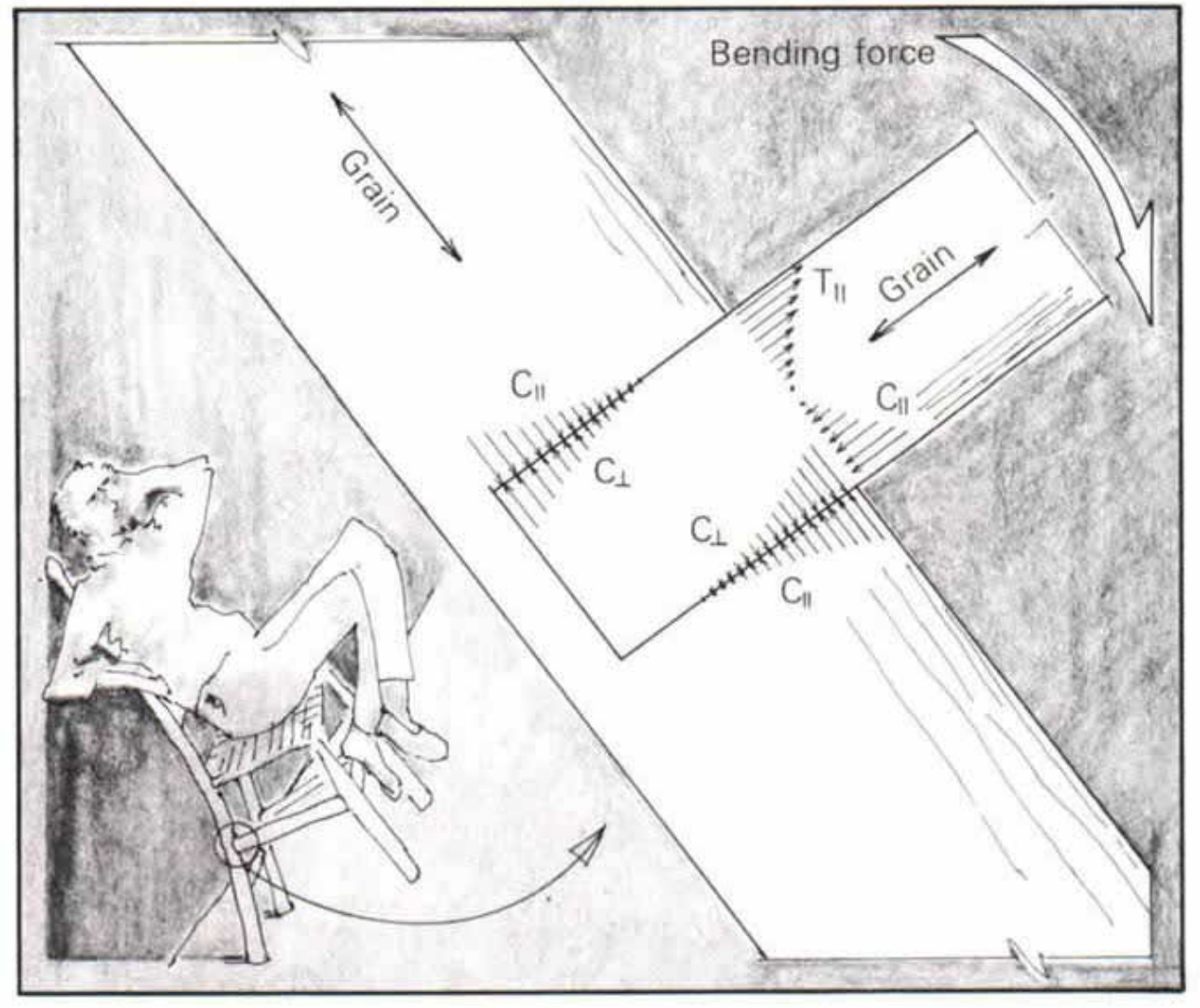

A plain round tenon in its simplest form, such as an unshouldered rung inserted into a chair leg, responds to external loading differently from a shouldered tenon, a dowel in a rail/stile frame joint, or a grooved, serrated or precompressed tenon. This article makes no attempt to address such special cases, but focuses on the individual dowel or tenon insertion. Obviously, the species of wood and the dimensions of a successful joint will accommodate the loads it must sustain. In a typical chair (figure 1 above), analysis can determine the dimensions and proportions of the joint so that axial stresses along the mating surfaces are safely within the strength properties of the wood. Adding glue provides shear resistance to whatever minor withdrawal load might be imposed. And the commonly used dimensions, which have evolved by experience and tradition, are more than adequate to resist loads imposed by use—or even moderate abuse. Chair rungs are rarely so small in diameter that they fail simply because of excess bending stress and break off at the joint. When they do break here, it is usually because the other end has fallen out of its socket, and someone then steps on the rung. Likewise, as long as the joint remains tight, its bearing areas are usually large enough to distribute the racking loads.

But two common shortcomings lead to problems. First, the mortise may be too shallow in proportion to its diameter. In a Windsor chair, for example, the thickness of the seat limits the mortise to a shallow hole compared with the rather large tenon diameter at the top of the leg. Second, the mating surfaces may be of poor quality. Poor turning or shaping of tenons is not nearly as common as badly bored holes. If the spurs of the auger aren’t in top condition, the surface of the hole is liable to be lined with damaged cells, which can neither support the bearing loads nor develop a successful glue bond. Proper fit is also critical. With water-based emulsion glues (white or yellow), highest withdrawal resistance develops when the dowel diameter is several thousandths of an inch less than the mortise diameter. If the tenon is oversized, the joint will be scraped dry upon assembly; if undersized, the glue line will be excessively thick.

From Fine Woodworking #21

From Fine Woodworking #21

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in