Fox Wedging

In this classic from the Fine Woodworking archive, learn about the fox-wedged mortise and tenon, a joint that is rarely used today but that has a long history.

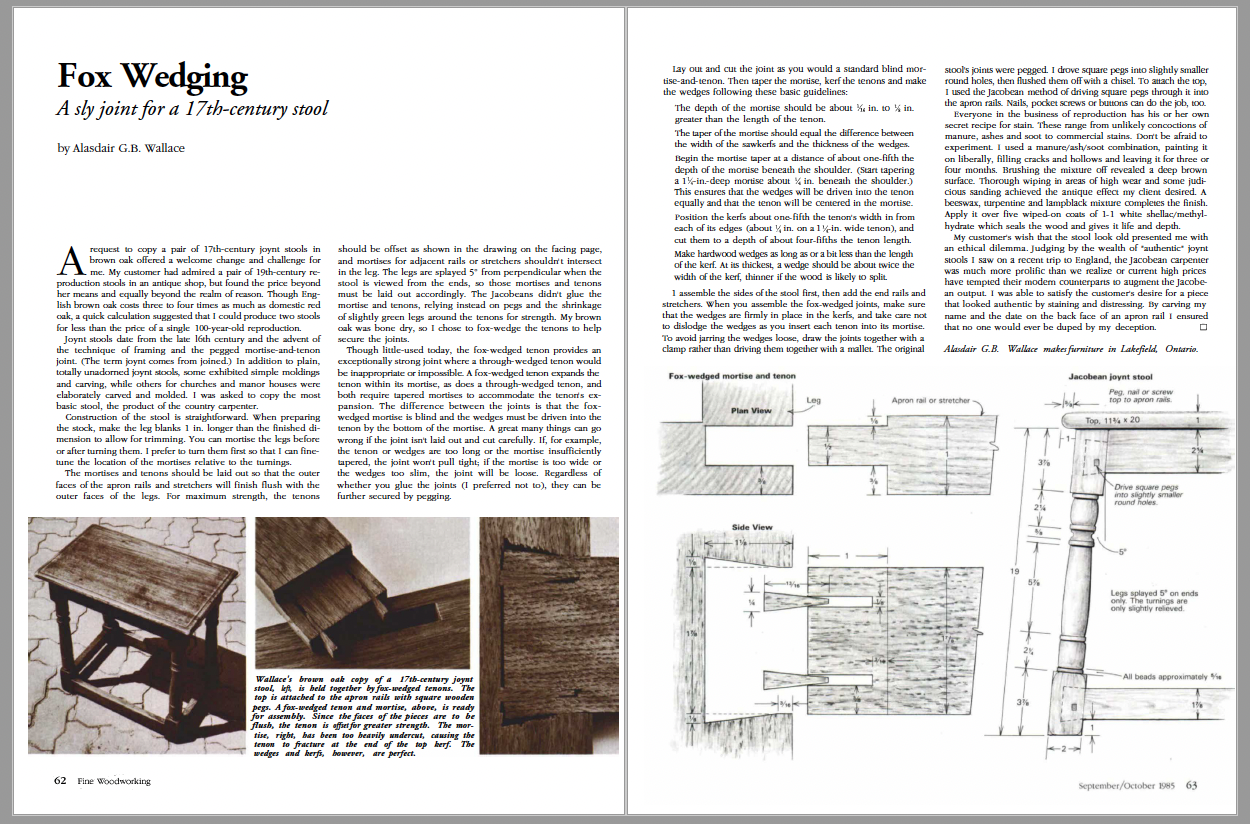

Synopsis: Alasdair G. B. Wallace made joynt stools using fox wedges, which expand the tenon within the mortise. The stools are traditionally made with green wood, which he didn’t have, so he substituted this old method. Fox wedging is similar to through-wedged tenons, though it uses blind mortises and the wedges must be driven into the tenon by the bottom of the mortise. He includes basic guidelines and assembly information along with drawings and photos that clearly illustrate how the joint works.

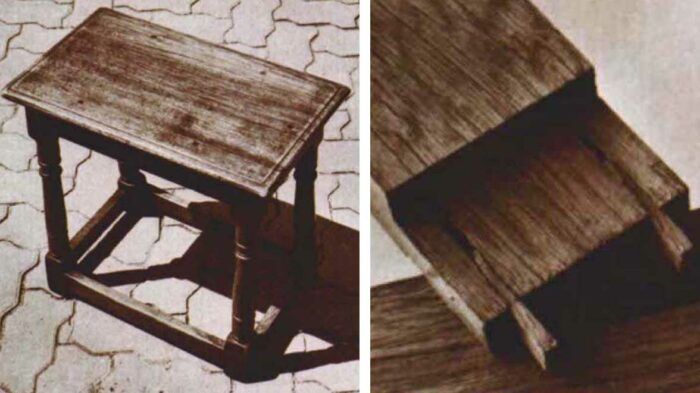

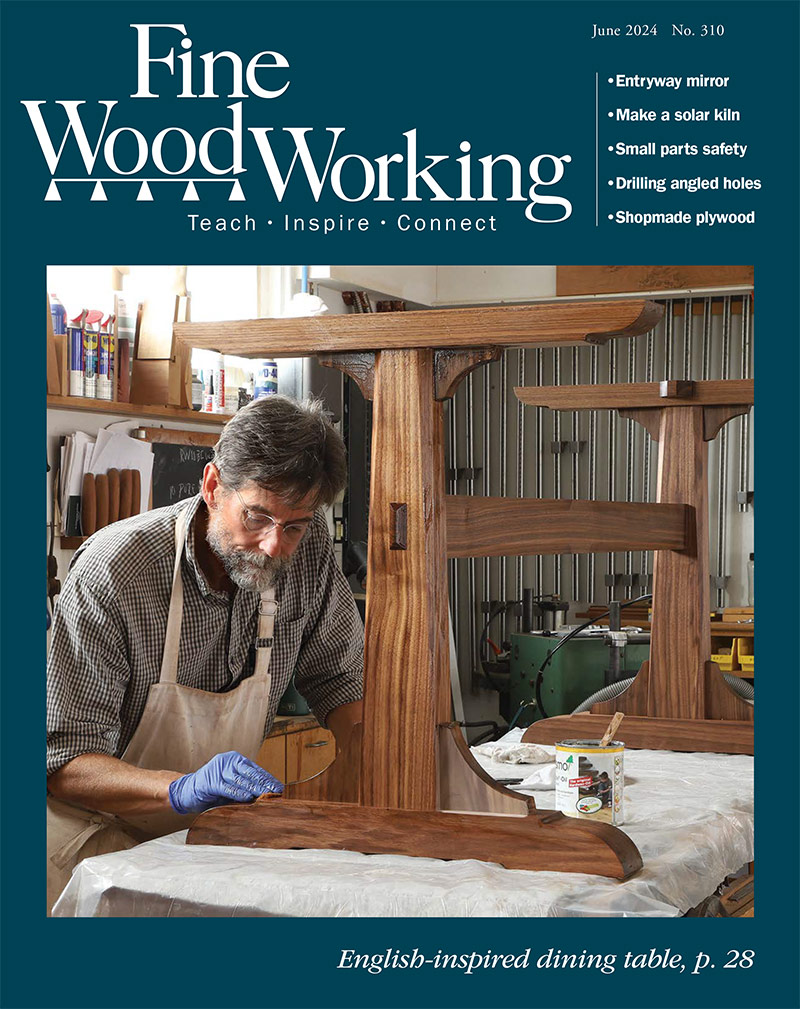

A request to copy a pair of 17th-century joynt stools in brown oak offered a welcome change and challenge for me. My customer had admired a pair of 19th-century reproduction stools in an antique shop but found the price beyond her means and equally beyond the realm of reason. Though English brown oak costs three to four times as much as domestic red oak, a quick calculation suggested that I could produce two stools for less than the price of a single 100-year-old reproduction.

Joynt stools date from the late l6th century and the advent of the technique of framing and the pegged mortise-and-tenon joint. (The term joynt comes from joined.) In addition to plain, totally unadorned joynt stools, some exhibited simple moldings and carving, while others for churches and manor houses were elaborately carved and molded. I was asked to copy the most basic stool, the product of the country carpenter.

Construction of the stool is straightforward. When preparing the stock, make the leg blanks 1 in. longer than the finished dimension to allow for trimming. You can mortise the legs before or after turning them. I prefer to turn them first so that I can finetune the location of the mortises relative to the turnings.

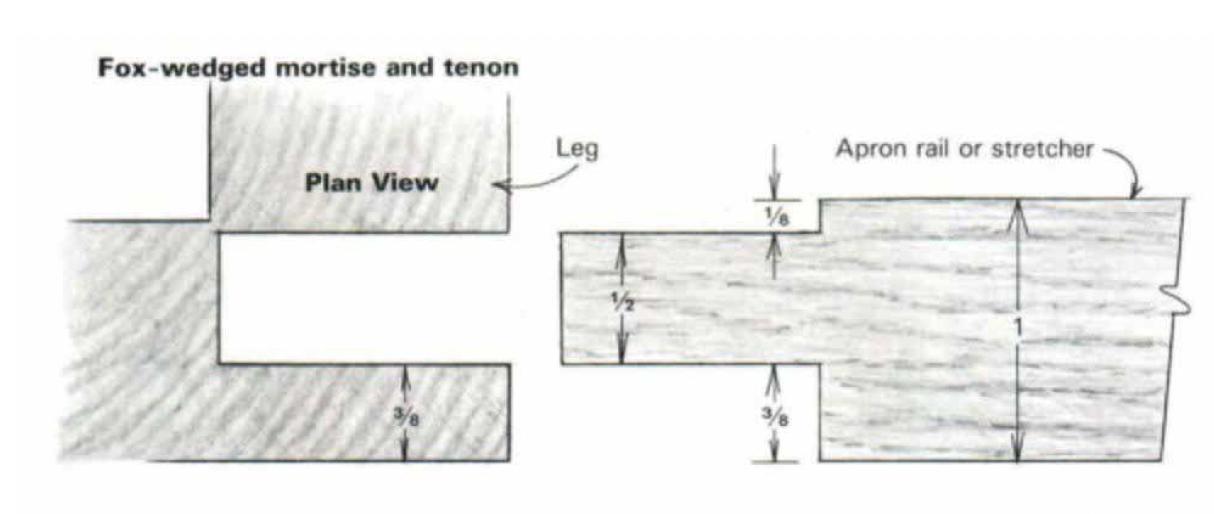

The mortises and tenons should be laid out so that the outer faces of the apron rails and stretchers will finish flush with the outer faces of the legs. For maximum strength, the tenons should be offset as shown in the drawing on the facing page, and mortises for adjacent rails or stretchers shouldn’t intersect in the leg. The legs are splayed 5° from perpendicular when the stool is viewed from the ends, so those mortises and tenons must be laid out accordingly. The Jacobeans didn’t glue the mortise and tenons, relying instead on pegs and the shrinkage of slightly green legs around the tenons for strength. My brown oak was bone dry, so I chose to fox-wedge the tenons to help secure the joints.

Though little-used today, the fox-wedged tenon provides an exceptionally strong joint where a through-wedged tenon would be inappropriate or impossible. A fox-wedged tenon expands the tenon within its mortise, as does a through-wedged tenon, and both require tapered mortises to accommodate the tenon’s expansion. The difference between the joints is that the fox-wedged mortise is blind and the wedges must be driven into the tenon by the bottom of the mortise. A great many things can go wrong if the joint isn’t laid out and cut carefully. If, for example, the tenon or wedges are too long or the mortise insufficiently tapered, the joint won’t pull tight; if the mortise is too wide or the wedges too slim, the joint will be loose. Regardless of whether you glue the joints (I preferred not to), they can be further secured by pegging.

From Fine Woodworking #54

From Fine Woodworking #54

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in