Files, Rasps, and Rifflers

Mario Rodriguez provides a guide to files, rasps, and other effective but underappreciated shaping tools.

Synopsis: There’s a lot to be gained by adding rasps and files to your tool kit: greater speed and control in shaping curved or sculptural elements, and dramatically reduced sanding time. No danger of tearout, either. The care and cleaning of these tools isn’t complicated, and in this article Mario Rodriguez explains how to do both. He talks about what they’re used for, what a basic selection of files and rasps includes, and what rifflers are.

Rasps and files have all but disappeared from most woodworkers’ toolboxes. Why? Well, there are a number of reasons. Routers and drum sanders do a lot of the shaping that rasps and files used to do. Because it’s easy to damage files and rasps, many woodworkers consider them more of a pain than they’re worth. And it can be hard to figure out what kind of file or rasp you need. What, for instance, is the difference between a second-cut patternmaker’s rasp and a bastard-cut mill file?

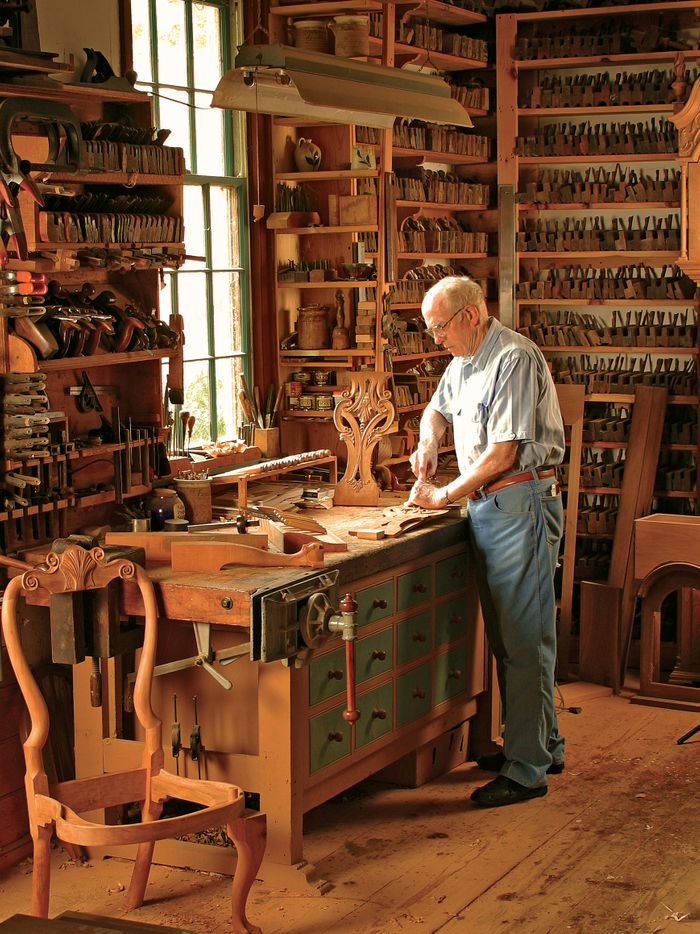

But much is to be gained by adding rasps and files to your tool kit: greater speed and control in shaping curved or sculptural elements and dramatically reduced sanding time. By using a succession of rasps and files, I can start sanding at 180- or 220-grit. And because individual teeth are doing the cutting, rather than a single blade, there’s no danger of tearout. Rasps and files are the fastest, most efficient tools for removing lots of material quickly, for fairing curves and for shaping furniture parts. Using rasps and files may be new to many woodworkers, but once you’ve started, you sure won’t miss all that sanding.

The care and cleaning of these tools isn’t complicated, as the story on p. 50 explains. And a basic kit of the most useful files and rasps doesn’t have to be expensive and can be assembled gradually.

What are rasps used for?

What are rasps used for?

Rasps actually can be considered a type of file, but unlike files, rasps have individual cone-like teeth, which are made by a punch striking the soft steel blank. These teeth are large and pointed, with deep gullets that keep the rasp from clogging. Each tooth and its gullet are formed with a single blow from the punch. This process is called stitching.

On some imported rasps, the teeth are hand-stitched, resulting in a slightly random pattern. Some woodworkers claim that these rasps produce a smoother cut with less chatter, but the handstitched rasps that I’ve used were no better than standard rasps that cost substantially less.

A rasp is the best tool for any sculptural shaping. It’s designed to remove bandsaw-blade marks or the facets left by a spokeshave, and it’s used to produce smooth, fair curves. You should always use the longest rasp that your task will permit. In the same way that a plane with a long sole is used to level and flatten a board, a longer rasp does a better job of smoothing dips or bumps in curved work than a shorter one will.

From Fine Woodworking #113

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below:

Comments

Good Article however since the article is aimed at beginners recommendation on quality tools like the one done on machine squares would be nice. It could mean the difference between tools that cut wood with ease vs frustration and choice french words

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in