Hand Tools for the Making

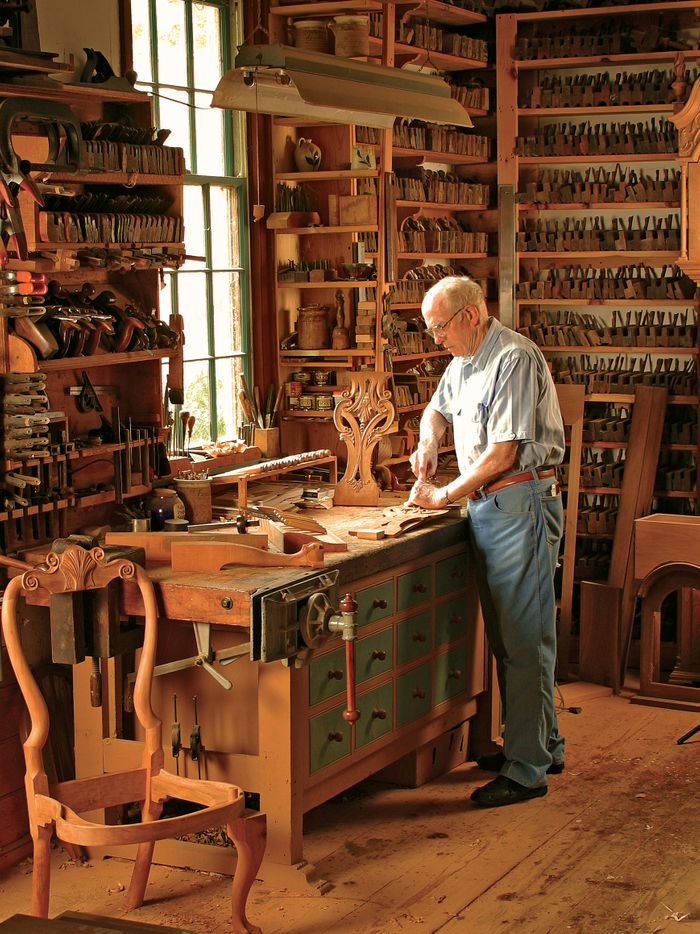

Irving Sloane makes hand tools for several reasons: to recapture the quality of days gone by, to meet the demands of special applications, and to improve on the designs available from mass-producers.

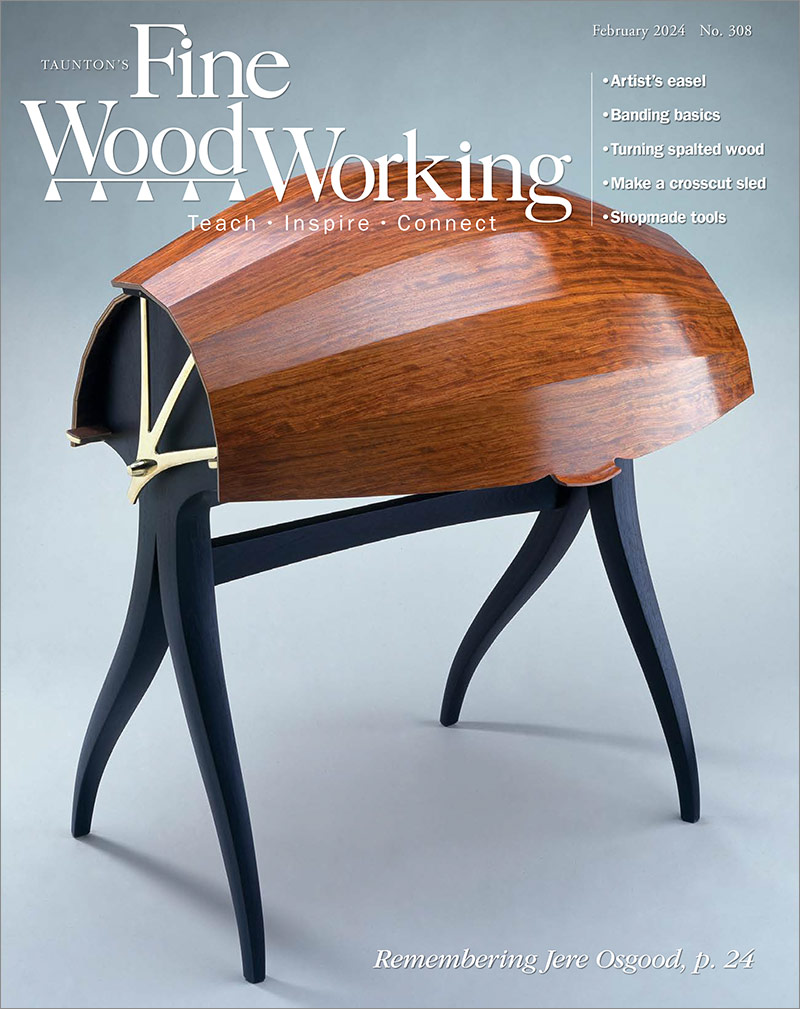

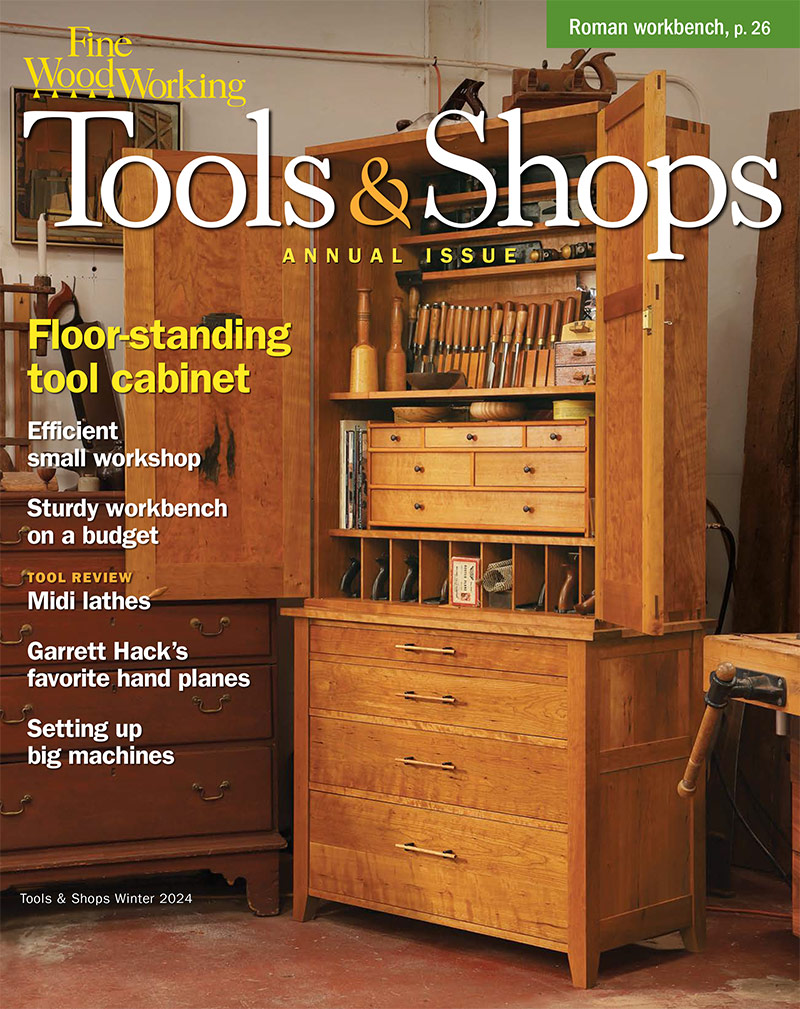

Irving Sloane makes tools for several reasons-to recapture the quality of days gone by, to meet the demands of special applications, and to improve on the designs available from mass-producers. The objects shown on the facing page recapture the combined elegance of function and appearance that every first-rate cabinetmaker once expected from his tools.

I am probably the only active woodworker with both a Norris and Primus smoothing plane gathering dust on a shelf. The reason for this curious circumstance is that I have built replacements that come much closer to my personal vision of what a plane should be.

I make guitars, working almost entirely with hand tools: a comprehensive collection of planes, saws, chisels, scraper blades and miscellany accumulated over 30 years. The scale of my instrument building does not call for heavy power tools, with their concentration-shattering din. Making musical instruments is essentially a quiet activity, a calming ambiance in which I draw great physical and metaphysical pleasure from planing, sawing, scraping and otherwise working wood by hand.

My idea of a good tool is a solid, well-made object that does the job it was designed to do. It should be comfortable to use and, I hope, look attractive. Finding hand tools that fit these particulars is not as easy as it once was. Power tools have pushed out many hand tools, and manufacturers have dropped others because turnover is too small by today’s high-volume standards. Lightweight plastics are fast replacing wooden handles (to the detriment of a handsaw’s balance), and high labor costs in industrialized countries will increasingly shift manufacture to low-wage countries, where price will be more important than quality.

The whole ethos of merchandising has changed since the days when tools of durable excellence streamed from the factories of Victorian Britain. Tool manufacturers then shared the universal assumption that having a good product was the high road to competitive success. Skilled journeymen, the “marketplace” back then, demanded fine quality; lesser tools made for dilettantes were whimsically described as “Gent’s” tools.

Today, competitive pressures focus on that end of the market where the preemptive word is not so much “good,” but “right” — the right tool, the right price, and the right merchandising. The appeal is aimed at the great mass of basically unskilled buyers who are building shelves in their garages. The choice of color for a plastic handle (involving market research and color consultants) is counted a weightier matter than the alloy in the blade. For these and other reasons, I came to understand that if I wanted my dream plane, I would have to make it myself.

I wanted tools that would not only function better than those on the market, but look beautiful too. Using planes as much as I do, I soon realized their shortcomings. The Norris smoothing plane, a famous example from the golden age of British tool manufacture, has deficiencies that make it less than wonderful today. The front grip is a brief stub of wood offering a restricted hand-hold, and the closed handle is designed for the three-finger grip favored by British woodworkers but alien to me. The screw-adjusted cap is inefficient — a half-turn too little can affect the plane’s functioning. The cutting edge is concealed from view and can easily strike the bottom of the fixed screw cap or the top of the mouth, and the mouth is not adjustable. The things I really like about the Norris are its heft, coffin-sided shape, thick blade and the configuration of the wooden frog. My own design for a metal bench smoother was based on these Norris features.

The wood-bodied Primus plane is a well-made German tool with a cumbersome adjusting mechanism. Removing the blade for sharpening is an above average bother, and replacing it involves complete repositioning of the blade using two knobs. I find the Primus’ horn-style tote unsatisfying in terms of comfort and control. As a plus, the mouth opening can be changed by simple adjustment of a wooden insert. I wanted my plane to have an adjustable throat, depth-adjustment without slack, lever-action blade cap for fast blade removal, and a lateral adjustment by means of a concealed device that could not be knocked askew.

I made many sketches, and tried different styles of tote and handle before constructing the metal bench smoother shown on the facing page. The patterns for the brass lever cap and malleable iron body casting were made of wood, with the bent sides made of maple veneer laminated over a curved form. Both of these, plus the pattern for the sliding toe piece, were sand castings. The regulating mechanism parts and cap lever were built of boxwood, and cast by a lost-wax foundry using inexpensive silicone molds. Steel regulator shafts and knurled brass knobs were turned by a machine shop. Precise hand-fitting of all the regulator parts eliminated slack motion. Wooden parts are Brazilian rosewood, the handle being a three-piece lamination. The blade is a 2-in. chrome vanadium replacement blade, 1/8 in. thick (available from Woodcraft or Garrett Wade).

For the wood-bodied plane, I used a laminate construction to avoid the difficult job of mortising the throat out of a solid block. Quartersawn teak was chosen for its dimensional stability, and the sole was lined with stainless steel. The metal lining is epoxied to the sole and secured with a “key” mortised into the front and back end of the body. These keys are hard-soldered to the sole plate. Loosening the screw in back of the tote permits movement of an insert in the sole to open or close the mouth. This plane is a joy, comfortable to work with for long periods and has the balance and heft that make it a good all -around plane. It holds a 1 3/4-in. chrome vanadium blade, 1/8 in. thick.

My total cost for four planes (jack and jointer in process) will average out to about $65 per plane . Not cheap, as planes go, but certainly a worthwhile investment to me. So far, I’ve built 22 tools — planes, trysquares, mortising gauges, bevels and spokeshaves. Good commercial chisels are not in short supply, so my chiselmaking has been confined to special-purpose kinds. I particularly like the exceptional comfort of a chisel-handle shape based on the handle of an engraver’s burin used in conjunction with a square instead of round ferrule. A square ferrule automatically orients the hand in its proper working mode. I plan about 10 more tools, including block plane, instrument-maker’s vise, level, hand router, and hand drill of improved design.

The time is not far off when China, India and other developing countries will be shipping basic hand tools of very acceptable quality to world markets. It is interesting to speculate that domestic producers may then abandon the homeowner market and choose to focus on tools for the skilled woodworker. We might see a bench plane that is not a Ford, but a Mercedes. In the meantime, I’ve found that it’s entirely possible to make your own tools using the best materials available, and without the cost constraints manufacturers have to live with. Not the least benefit of surrounding yourself with elegant tools is the constant stimulus to do work that measures up to the tools.

From Fine Woodworking #63

He was 73. He wrote several books on guitar construction, and these, too, focus on the benefits of making special-purpose tools.

Making his inlaid bevel gauge was described in FWW #60.

Photos by the author.

Comments

Is there only the one photo? More pictures of Sloane's tools would be very welcome, if you have any. Also comments from today's woodworkers on how things have changed in the last thirty years.

As a former member of the the Guild of American Luthiers, I wish to correct the editors on Mr Sloane description.

"Irving Sloane, noted author on the art of lutherie, passed away on June 21, 1998, following a three-year battle with renal cell cancer. He is survived by his wife, Zelda Sloane, his children Roy, Linda, and David, and four grandchildren."

He is also credited for engineering quality tuners for both classical guitars and Contra Basses.

I'll make those changes. For the record, as noted at the top of the page, this article is from 1987.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in