Choosing and Using Japanese Handsaws

In this classic article from the archives, Toshio Odate introduces Western woodworkers to Japanese handsaws.

Synopsis: Sculptor and woodworker Toshio Odate describes general-purpose and specialized Japanese saws that are useful to cabinetmakers. He also explains how to cut with each one. He shares history on Japanese saw design and sawtooth configuration and then details the ryoba-nokogiri, dozuki-nokogiri, azebiki-nokogiri, kugihiki-nokogiri, and saws with changeable blades.

I remember the first time I went to Atlanta, Ga., to lecture on Japanese woodworking tools. I packed most of my tools in my luggage except my saws. I kept them with me because they were fragile. But when I tried to carry them through the gate to the airplane, I was surrounded by security guards. They did not believe me right away when I explained that the peculiar-looking saws I carried were actually woodworking tools.

Perhaps it was the exotic appearance of Japanese saws that first caught the eyes of many Western woodworkers when these tools became popular in America around the early 1970s. But even though the Japanese planes and chisels that appeared around that time gained rapid acceptance, many Westerners who first bought the saws were disappointed with the results. That isn’t surprising because these saws are very different from their Western counterparts. Also, there wasn’t a lot of information available at that time about how Japanese saws should be used.

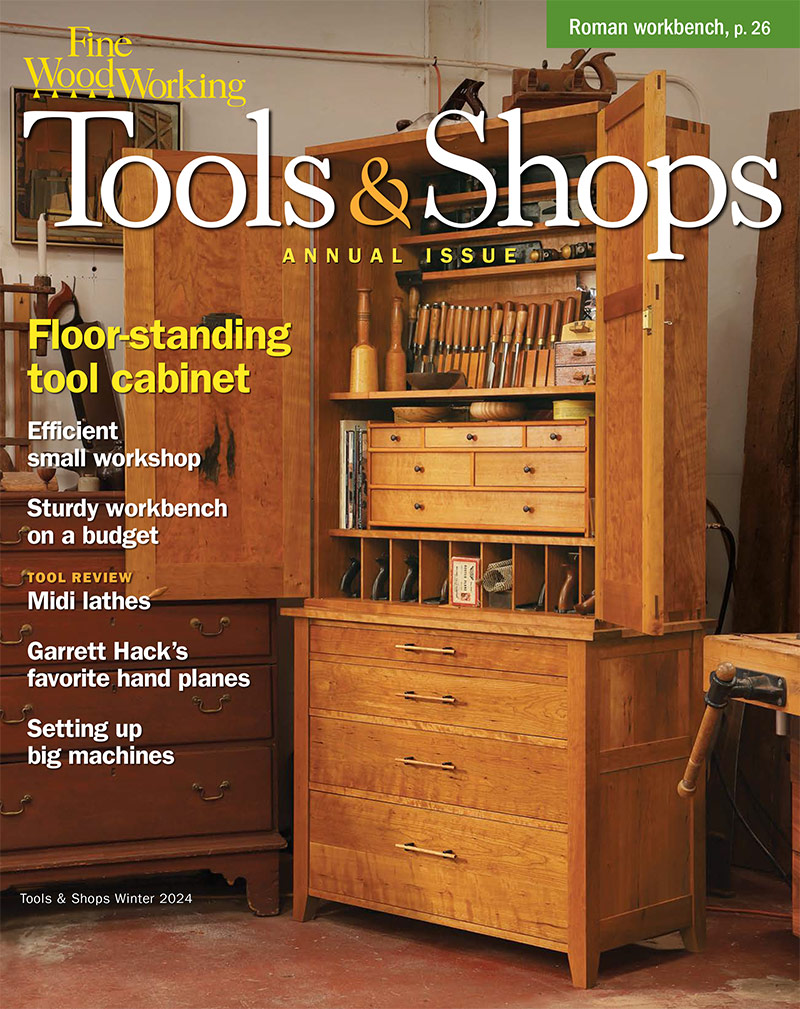

I will describe several Japanese saws that are most useful to cabinetmakers, including more general-purpose saws, like the ryoba-, kataba-, dozuki-nokogiri (nokogiri or just noko means saw in Japanese), as well as more specialized saws, such as the azebikiand kugihiki-nokogiri (see the photo above). I’ll also describe how to properly take a cut with each one.

Japanese saw design

Unlike Western saws, which cut on the push stroke, Japanese saws all cut on the pull stroke. Sawing with a pulling action allows you to cut using both arms and the muscles of the entire body, without having to put your body weight into the stroke. This suited the traditional Japanese shokunin (craftsman) who typically worked in a squatting or sitting position. Because a Japanese saw is put into tension during cutting, the blade can be made very thin and from harder steel, so teeth stay sharp longer. Furthermore, a thin blade removes less material, so it requires less power to use.

The teeth on Japanese saws work on the same principle as their Western counterparts but have some important differences. Rip teeth are graduated, so they’re smaller at the blade’s heel (near the handle) and larger at the toe. Crosscut teeth remain the same size along the length of the blade but have an extra bevel on top. The angle of the teeth and top bevel of crosscut teeth also vary, depending on whether the saw is made for cutting hardwoods or softwoods.

From Fine Woodworking #101

From Fine Woodworking #101

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below:

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in