Twin screws for everyone!

Many of the classes Megan Fitzpatrick teaches involve large dovetailed carcases, and while you don't actually need a Moxon vise to make them, it sure simplifies things.

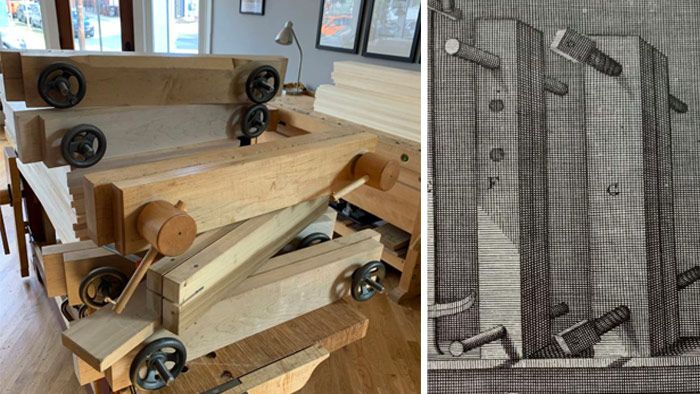

Many of the classes I teach involve large dovetailed carcases (tool chests … lots of tool chests), and while you don’t actually need a Moxon* vise (aka a portable twin-screw vise) to make them, it sure simplifies things.

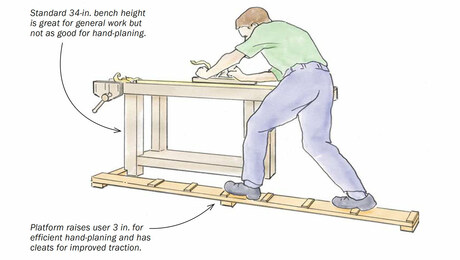

My workbench, at 31 in., is my optimal height for handplaning. I can get my entire upper body over the work and basically lock my wussy arms in planing position, then rock back and forth using my much stronger butt and thigh muscles to plane. This allows me to plane for a relatively long time without getting worn out. When I have to plane on a taller bench and thus use my arm muscles more, it takes me a lot longer to get the work done because I take many rest periods. The tradeoff, however, is that my bench is too low to be comfortable when sawing.

Arguably, you can use a leg vise (or whatever vise is on the front of your bench) to raise the work (and sometimes I do that if I have only a quick cut or two to make). But by the time the work is high enough to be in the optional sawing position (basically, even with my elbow when I’m in sawing stance), it’s not sufficiently supported, so the work chatters. That makes it difficult to saw quickly and accurately – and I don’t want to add any unnecessary difficulty during classes.

With the work clamped in a vise that’s clamped to the top of the bench, I can get it in the right position and have it fully supported across its width for easier and more comfortable cuts.

This big vise isn’t likely a daily user, which is why I prefer it be portable rather than integrated into the bench. Whenever I work on a bench with a twin-screw vise on the front, it gets in the way of planing. But when I do need it, it’s invaluable.

The benefits exceed simply working more comfortably. The thick jaws easily clamp out any slight cupping in the material, which is often a problem in wider stock.

|

|

|

Pulling the cup out of the pieces makes for far more accurate joinery—particularly when making the cuts, and when transferring tails to the pin board (yet another reason to cut tails first!).

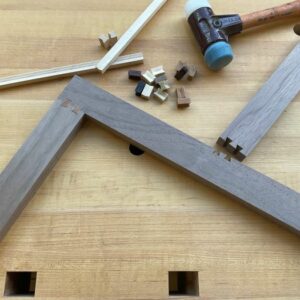

Here’s a trick to get the work clamped level in the Moxon vise, and have everything set up for tail transfer: Cut a block of wood that is the same length as the height from the benchtop to the top of the vise (in my case, 5-1/2 in., plus the thickness of one of your handplanes (and mark it so you don’t throw it away). Or better yet – though I have yet to do this – cut a block that is 1-3/4 in. square by 7-1/4 in. long. (1-3/4 in. plus 5-1/2 in.). Then, you can use the block to position the workpiece in the vise, rather than a plane. (Note that your measurements could vary, depending on the height of your vise’s back chop.)

Again, you don’t need a Moxon vise to cut dovetails – but I’m all for anything that makes work easier, more comfortable, and most accurate. That goes doubly so in a classroom situation, and that’s why we have six of these portable vises in our shop; there’s one for every student (plus one on the front of our Holtzapffel bench).

— Megan Fitzpatrick

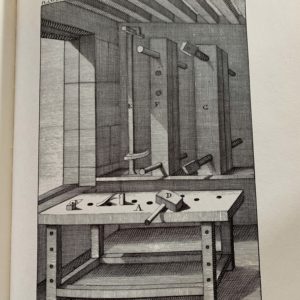

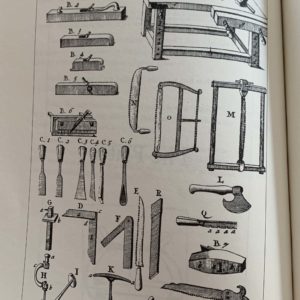

* “Moxon vise” is a bit of a misnomer. While it shows up in Joseph Moxon’s “Mechanick Exercises,” (1703) Moxon likely borrowed it from Andre Felibien’s “Principes de l’architecture” (1676) and it likely predates Felibien, too.

Comments

I disagree with the assessment that the moxon vice is on the wrong end of the bench in the drawing. That position allow a right-handed person to stand next to the bench and use the right hand to plane along the side and the end of the bench. I am sensitive to this because I am left-handed and built my own bench in the opposite configuration.

Tradition would conflict with what you say, but there’s nothing wrong with setting it up how it best suits you.

Cheers

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in