The business of curvature

For David Haig, design begins with a lot of sketching, and slowly, from the jumble of ideas, something begins to take form.

Designing anything new is a strange process because the origin of ideas is so fundamentally mysterious. But there are well-worn pathways, and like many I usually start with a lot of sketching and slowly, from the jumble, something begins to crystallize.

Sometimes it’s an image, sometimes just a line or a thought, but some quality suddenly resonates with the initial question or impulse. It can feel like a homecoming after a long absence, some warmth, almost familiarity as the door is approached. As a piece emerges in the mind with all its complexity and potential, questions and doubts often arise, too: Can I do this? Is my level of skill and understanding adequate? And, most crucially, is this idea worth the weeks of work, burning through expensive and sometimes rare materials, the costs on every level that committing to making something meaningful entails?

The design apart, when it comes to construction we woodworkers are on more solid ground. We can learn how to assess the suitability and refinement of the construction of any piece based on long traditions as well as contemporary understanding of wood and wood engineering. Whether a piece is built using a CNC or hand tools, if it’s of wood, there are joinery and construction choices to be made—good, less good, and some outright bad.

There are always these powerful but somewhat contradictory forces involved in designing and making. But this friction may be what powers up the whole enterprise and makes it worthwhile.

Strategy For Curved Panels

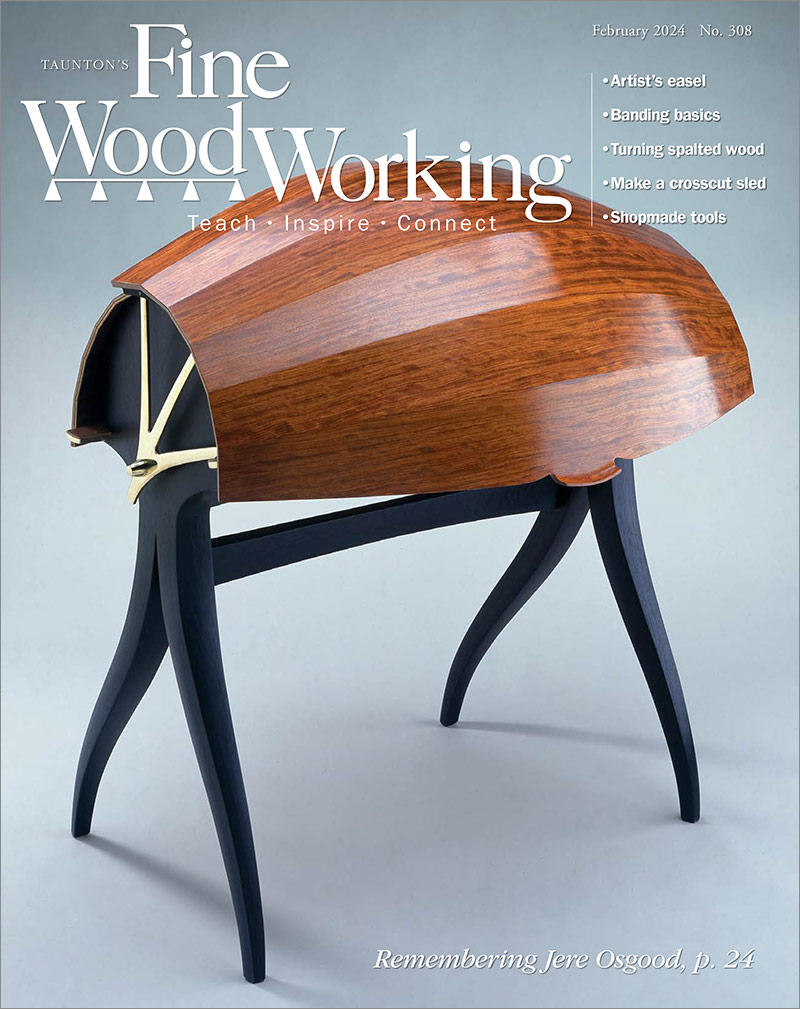

A good idea sometimes fails for want of a suitable technique, which is why technical understanding is so valuable. A problem I worked on for some years was how I could make wide, tapered panels look as natural and unforced as possible. My Andromeda coffee table (left photo, below) was the first result of that exploration, and Sally’s Hall Table (right photo) was the second. I ended up writing a full article on the technique, “Curved Panels for Furniture,” FWW #231, where I explain how I make the kerfed, curved tapered panels and how to cover the edges that showed the kerfing cuts. With the edging my ability to steam-bend came into play: I cut edging strips from the same plank as the facing wood so the grain would match, and then steam-bent them to follow the curve. When done carefully, the effect was exactly as I wanted, and it was not easy to detect that the panels were other than all solid wood. I use solid wood whenever possible because you can shape it as you please, without the fear of exposing gluelines.

A good idea sometimes fails for want of a suitable technique, which is why technical understanding is so valuable. A problem I worked on for some years was how I could make wide, tapered panels look as natural and unforced as possible. My Andromeda coffee table (left photo, below) was the first result of that exploration, and Sally’s Hall Table (right photo) was the second. I ended up writing a full article on the technique, “Curved Panels for Furniture,” FWW #231, where I explain how I make the kerfed, curved tapered panels and how to cover the edges that showed the kerfing cuts. With the edging my ability to steam-bend came into play: I cut edging strips from the same plank as the facing wood so the grain would match, and then steam-bent them to follow the curve. When done carefully, the effect was exactly as I wanted, and it was not easy to detect that the panels were other than all solid wood. I use solid wood whenever possible because you can shape it as you please, without the fear of exposing gluelines.

|

|

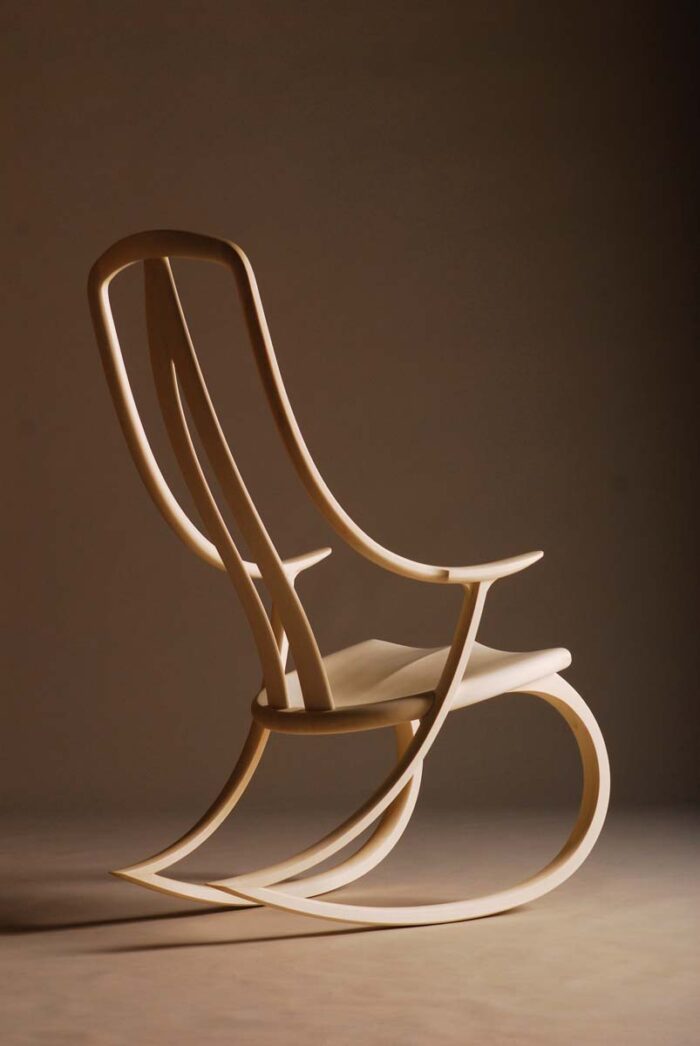

Monogram Rocker

My Monogram rocker involved an intense creative process. Designing it became an obsession with months of feverish sketching. One morning the missing line came into focus, and that strange sense of homecoming arrived.

I had the desire to build a rocker that was truly fluid but also crisp and minimal. It is certainly much easier to design within the bounds of some well recognized stylistic reference, for instance Mid-century Modern or Arts and Crafts. This gives plenty of hooks and pegs to hang your ideas from, and for other people to relate to.

I was lucky and sold the first rocker. Building the second was harder because I was not buoyed by the same degree of wonderment and surprise, and I had to rework the parts of the chair that were not good enough. Over the next 30 years, I’ve made close to 300, a number that even now seems inconceivable. With countless refinements along the way, the chair is now a much better resolved piece. But amazingly, the initial design in its essence remains unchanged.

Evolving Design

I’ve seen in many designs how the ideas expressed looked only partly complete, as if the designers had moved on to new ideas before they fully explored and resolved their earlier ones. It is to avoid this that good makers of music or art (or anything really) frequently work through themes or series, refining with each new iteration.

|

|

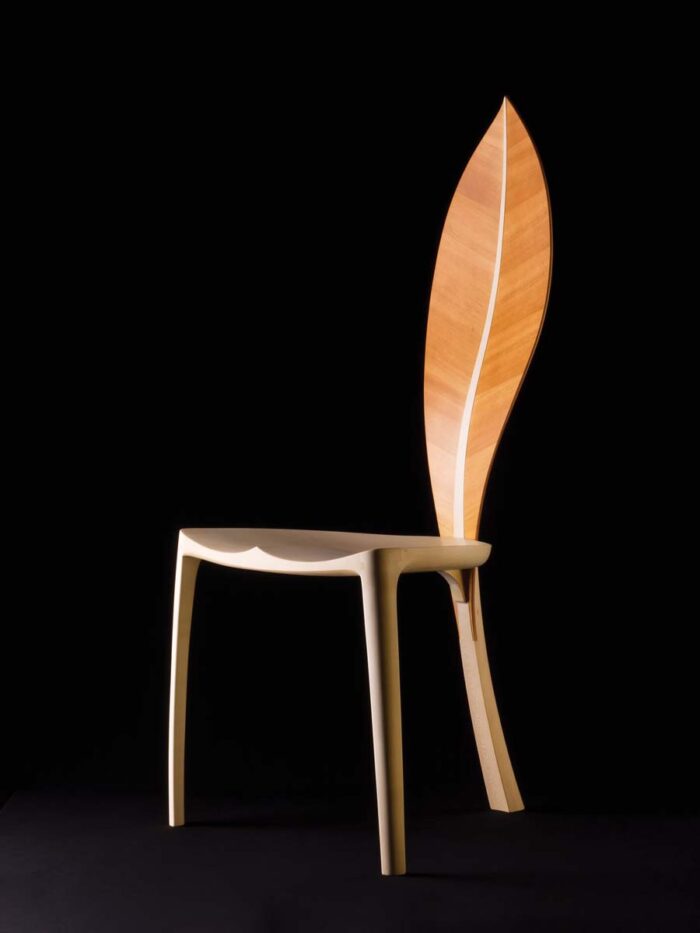

In the case of my Folium chair, I’d been attracted by the idea of a leaf shape for a backrest for many years and had at one point tried to integrate the idea into my rocker. It was difficult to attach the two halves of the leaf onto a re-curving central spine, but the comfort and strength seemed outstanding. I decided the leaf was wrong for my existing rocker, but the leaf idea remained.

I designed my first three-legged chair around 2000 and called it my V chair (top photo). I refined it over several more years and have made several sets of six or eight, even one of 12, and it’s proved that three legs, if properly spaced and splayed, are just fine for stability, and lend a special poise and elegance. Then in 2014, in a simple flash of recognition, I saw that a three-legged chair was the perfect form for building a chair with a leaf-shaped back, as the stem could naturally form the single rear leg. The chair’s front and seat were already well resolved in the V chair, so with a little tweaking, I could graft the leaf idea onto it. It was an exciting moment, and one where a simple sketch pretty much encapsulated the whole piece.

In another case of a design coming together over time, with my Orpheus bench (above), four years separated the seat from the back. I completed a tunnel-shaped bench during an artist residency at the Center for Furniture Craftsmanship in Maine in 2019. Four years later, when I got a second invitation to CFC, I completed the backrest. The tunnel shape was my initial goal, and once that was built, I left it in storage, but it did not feel completed. My task was clear: It needed a backrest, and the question was how to add this in an integrated, but bold and unfussy way. Drawing the sweeping curves running through the sides and up to support a backrest was another of those breakthrough moments, and the shape and form of the backrest followed without too much struggle.

Lockdown Cabinets

These paired Lockdown cabinets were my commissioned project during our Covid lockdown and were one of the reasons my memories of that time are such happy ones, as grossly unfair as that sounds. They were a sort of take on Arts and Crafts, perhaps Charles Rennie Mackintosh, riffing on the interaction of curves with squares and rectangles, except these curves were parabolic not radial. Very satisfying pieces and one of the few times I’ve successfully used the timber provided by a client—in this case wild English cherry, garden grown.

Blanket Chest

This blanket chest in Pennsylvania black cherry was a wedding gift for my middle son and his wife, and like the writing desk, it has curves that were subtle enough to require almost no steam-bending. The front and back panels were shopsawn veneers applied to thin flexible panels, but the top and sides were solid cherry. The top was curved to form a seat shape, comfortable for putting on socks and shoes at the foot of a bed. The difficult part was fairing in the top of the solid panels to the curves of the mortise-and-tenoned frame where side grain abutted end grain.

-David Haig is a furniture maker from Nelson, New Zealand.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in