Synopsis: Jere Osgood continues his series on bending laminate. This article focuses on layers of wood that are not of uniform thickness — tapered laminations and double-tapered lamination. He explains how these techniques permit you to make a curved piece whose width and thickness vary. His methods may appear fussy, but he says they will appeal to assemblers and people who enjoy complicated joinery. He also includes some notes on laminating that discuss making press forms, aligning parts, and design simplicity.

From Fine Woodworking #14

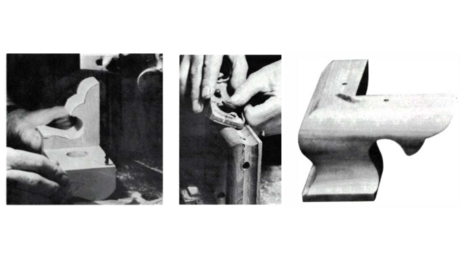

Thin layers of wood are easy to bend. Several thin layers, all with the grain running in the same direction, can be bent on a form and glued together. The resulting curved laminate is much stronger than a piece sawn from solid stock would be, and much less wasteful of material. It is also stronger than a steam-bent piece, because the glue adds to the strength of the wood. Lamination has the additional advantage of stretching rare or highly figured boards, since the best stock can be resawn and used to face all the legs of a chair or table. I discussed the basics of simple bent lamination, the necessary forms and the gluing techniques in the Spring ’77 issue of Fine Woodworking (pp. 35-38). This article will cover layers of wood that are not of uniform thickness—tapered laminations and double tapered laminations. These techniques permit you to make a curved piece whose width and thickness vary, whereas a simple bent lamination can vary only in width. If the design requires cutting through the thickness of a layer of wood at any point along a curve, the whole part is weakened. The severed layers no longer contribute to the strength of the assembly. The problem is avoided by tapering the layers of wood, so the variation in thickness is built right into the lamination. It is important to make each layer of wood as thick as possible although still thin enough to follow the desired curve. It is much better to resaw stock to optimum thickness than to use many layers of thin veneer.

I know that my methods are liable to appear fussy or confusing to people who are accustomed to bandsawing curves from heavy, solid stock, but they will appeal to assemblers and people who enjoy complicated joinery. I prefer to spend time on the planning and drawing, instead of on carving huge amounts of waste from unformed heavy stock. Once a curve has been laminated, it is hard to alter the outward shape. It is simple to revise the shape of a bandsawn part. Because accurate previsualization comes with experience, I don’t find being locked in a disadvantage. When I teach, I mention many times the absolute necessity of making full-size shop drawings. Many part-time woodworkers don’t do this, but it is the key to seeing the shape of the finished, three-dimensional object. And it is the only way to be sure from the start that the joinery is possible.

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in