Scandinavian styles

1978 Den Permanente exhibit features Krenov and other Copenhagen cabinetmakers

Editor’s note: This article from Issue #12 is one that was previously unavailable in the online archive. Following its mention in a recent Benchmarks First Person feature, we thought it would be of interest as a throwback piece. If you’re curious about any other legacy content, you can find older issues in our Magazine Index.

In May 1978, Den Permanente (The Permanent Exhibition of Danish Arts and Crafts) of Copenhagen put up two exhibitions, each a gem of its kind for anyone interested in the fine art of cabinetmaking. One was a display of 66 items made by nine master-craftsmen in Copenhagen. All the designs were originally introduced at the annual exhibitions of the Copenhagen Cabinetmakers’ Guild from 1927 to 1966. The other, smaller exhibition was a series of one-of-a-kind items by James Krenov, Sweden’s artist-cabinetmaker. Although both exhibitions offered furniture of high artistic quality and superb craftsmanship, there is a world of difference in the process by which the two categories of furniture originated and in the philosophy behind them.

When the Copenhagen Cabinetmakers’ Guild hit upon the idea of staging an annual exhibition in 1927, it was by no means because the craft had much to boast about. On the contrary, there was a strong feeling that with the rise of industrial production, the times were moving against the craft. But farsighted members believed that an annual showcase of this kind could be used as a lever to turn the tide. The next generation would be using the term “product development.”

There is very little from those early years that manufacturers hold up with pride. But gradually, as the annual exhibitions found their final form and became a regular furniture feature, a useful relationship was built up between the cabinetmakers and outside designers. The gap widened between the mind that conceived the furniture and the hand that made it. But this alliance of mind and hand contained the first seeds of the Golden Age of Danish furniture-making in the 1950s and 1960s, the era of the “big-name” designers. The Guild exhibitions thus became the nucleus of a peaceful contest of skills between the best in the industry, an event that encouraged the investment of extra effort and the blooming of high hopes. Of course, contemporary critics complained (as they do of the more industrial Scandinavian Furniture Fair today) that nothing was happening. But looking back over those years via Den Permanente’ s exhibition, you see that in fact a lot was happening.

And in retrospect we see the exhibitions had an effect the organizers had scarcely anticipated-and certainly did not wish. The annual displays became a source of inspiration for the very industry they were designed to keep at bay. And today many items of industrially manufactured furniture can be traced directly back to cabinetmaker’s models introduced at Guild exhibitions. Some of these industrial items were also on show at Den Permanente. In 1966, after an uninterrupted period of 40 annual exhibitions, the Copenhagen Cabinetmakers’ Guild suspended these events on account of a wavering economy. Since then, many have tried to revive this important activity, so far without success.

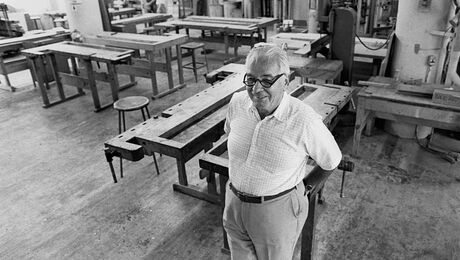

James Krenov, no doubt a familiar name to readers of Fine Woodworking, has established a reputation on two fronts: as an exceptionally original cabinetmaker and as an industrious lecturer and writer (A Cabinetmaker’s Notebook and The Fine Art of Cabinetmaking, both published by Van Nostrand Reinhold, 7625 Empire Drive, Florence, Ky. 41042).

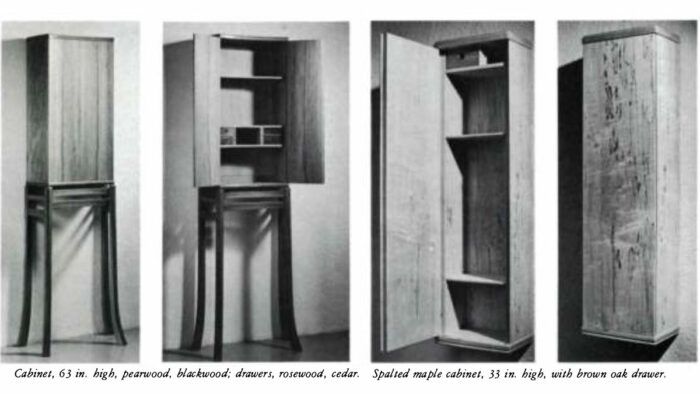

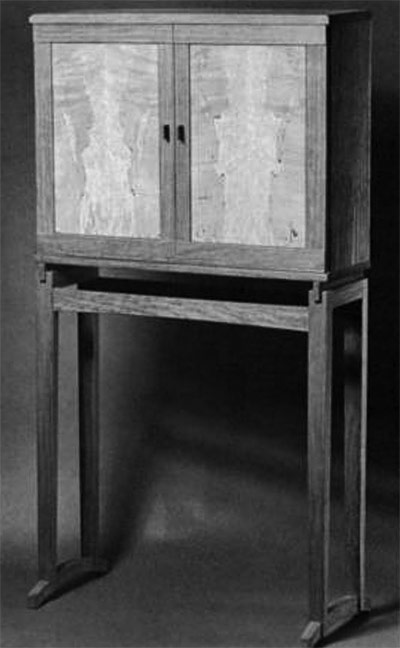

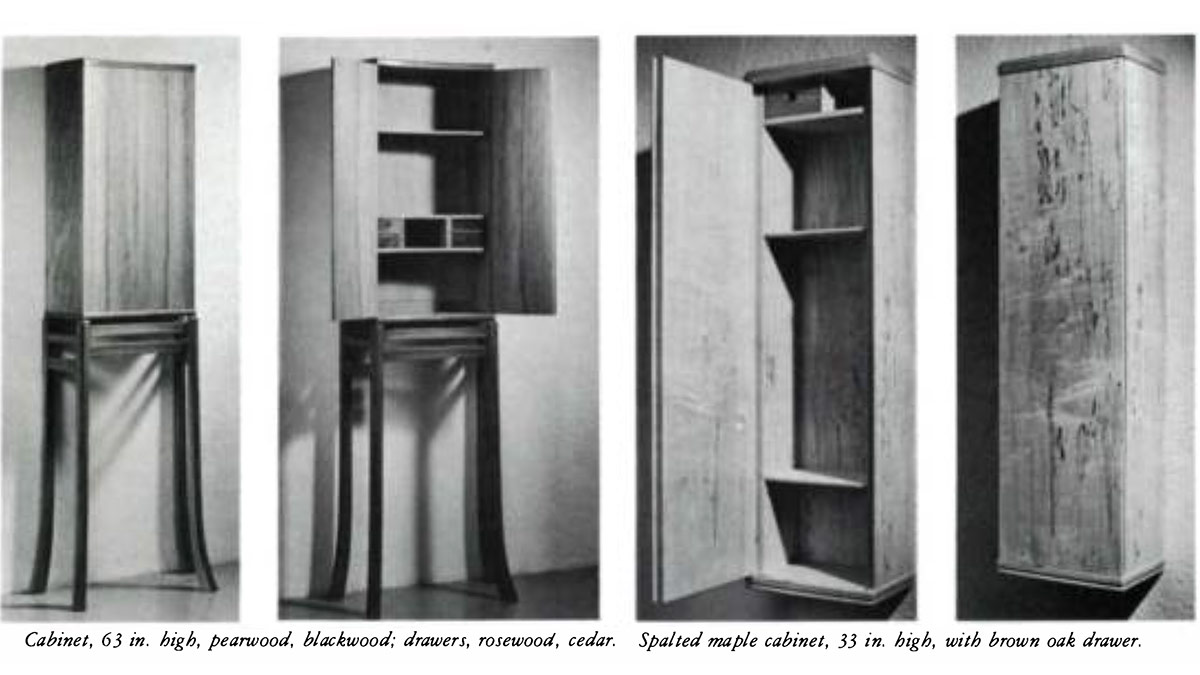

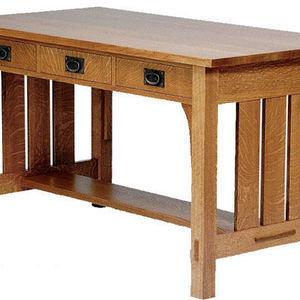

Den Permanente’s show included 16 pieces by Krenov. Some of them are shown above.

Normally the word designer is applied to the person who decides the form of an object. These days the designer is not likely to be the person who then physically makes the object. As suggested earlier, this separation of mind and hand was an important part of the background to the worldwide success of Danish furniture-making a decade or two ago.

In Krenov’s case, it is difficult to use the word “design” at all. True, he decides the form and so to some extent may be considered the designer, but the precise, final form is not predetermined—it emerges from the dialog between master and material as the work proceeds. With Krenov, design is a consequence of the type and nature of the wood; design stems from a love-indeed a veneration-of his material. It will be obvious that each Krenov item is unique.

Can Krenov justify his approach to cabinetmaking in an age when we coldly, deliberately bend nature to our will, and even destroy it in order to satisfy the most vulgar, artificially created “needs?” The question, of course, is strongly biased, and the answer can only be yes. Apart from reminding us that he who really conquers nature is himself doomed to lose, Krenov discreetly teaches us the natural potential of wood. The solution to a timber problem may be surprising and logical, if you are wide awake. Take, for instance, Krenov’s small writing table: The drawer opens on the right, so the user doesn’t have to move the chair backward in order to take out paper or pen.

Krenov plainly does not make furniture for the masses. But his furniture brings a message that no one working with wood would be advised to ignore.

|

A modern bench |

|

Professor Frid |

|

A Love of the Craft, Exposed |

Comments

In viewing a collection of Krenov’s work, one might conclude that he had a bad back and did not like to lean over

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in