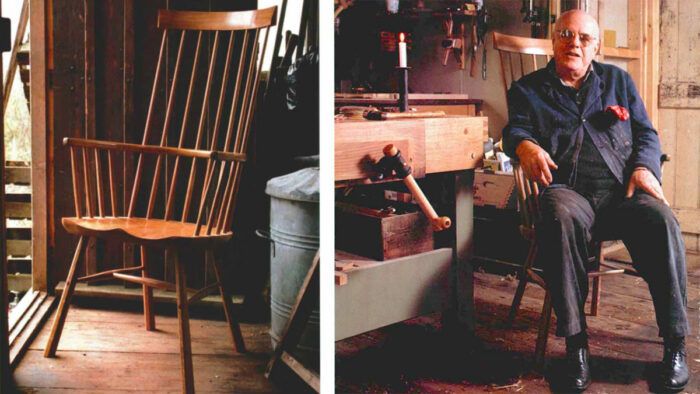

Good Work

Outspoken and unapologetic, a Welsh chairmaker makes a plea for hand tools

Synopsis: John Brown eloquently describes his love for woodworking using hand tools and points out the benefits of following suit. Any attempt to summarize his arguments loses his poetry, but here are his main points: using hand tools saves materials and prevents you from being surrounded by noisy, dusty, ugly machines. Machines were introduced to woodworking to aid quantity, not quality. Classroom time is no substitute for apprenticeship, and the human touch adds soul to a finished piece.

My grandmother used to tell me that most of life’s ills were caused by men chasing money. Even 50 years ago, the poor old dear could not understand what all the rush was about. She had a theory that the heartbeat hadn’t altered since time began and that the pace of life should be regulated by this fact. I didn’t take any notice of her at the time, but recently, I’ve had cause to recall her words. The speed of modern life is out of synchronization with the human body. If we could slow our lives down a little, think of quality before quantity, there would be more time to savor the pleasant things before we are forced to rush on to something else.

Woodworkers are not excused from this malady. Every bit of literature, every handbill or periodical to do with the craft is packed with advertisements for machines. A young man interested in making things out of wood can be forgiven for believing that machines are a fundamental necessity. Hand tools have been relegated to the small advertisement section or antique dealers, as though they were relics of the past whose use went out with grandfather.

Save materials, and stay comfortable

The price of timber once seemed of little consequence. Now, with rain forest problems and a general scarcity, this has become a very expensive raw material. A return to the use of hand tools, apart from being less wasteful, would add more value to this precious material. I fully appreciate the average woodworker cannot render tree trunks into planks. Handsawing huge bulk is pure sweat, so the use of a power saw is necessary. That is all that is required to lead a full and satisfying woodworking life.

Power machines are unfriendly, for they are very noisy and make a lot of unpleasant dust. Craft woodworking should be a creative activity, with the practitioners as artists. Surrounded by ugly, noisy, dusty machines, the woodworker does not have the environment in which to do good work.

There are two main health hazards from frequent use of machinery, apart from cutting off the fingers: dust and noise. Neither is instantly apparent, as is an amputation, but nevertheless they are just as dangerous. The most frightening is nasal cancer, which is closely associated with wood dust. And constant exposure to high levels of noise can damage the ears and lead to deafness.

Of course, you can wear protective clothing and apparatus against these ills. But to mummify yourself in this way can only be to the detriment of careful work. Picture, if you will, a cabinetmaker working on a fine piece of oak furniture clad in a hard hat. I am sure the sense of control of the operator is impaired by wearing all this safety equipment.

Machines aid quantity, not quality

The reason for the introduction of machinery in the 19th century was to speed up the production in the factories. Water, then steam and, finally, electricity provided ample power, and in that great age of innovation, machines were invented to cope with more and more process. The owners cared not a jot for design or quality unless it affected sales. Quantity was the main criterion. “How can we make more profit?” they asked Unskilled people could be trained to work a single-operation machine in days. The fact that these operators had no interest in their work and did the job for what money they could get interested no one, except people like John Ruskin, C.R. Ashbee and William Morris.

Since the last great war, it seems that these same principles have been adopted by modern woodworkers. Yet the motivation is entirely different. I have never known a craft woodworker who does the job only for money, or at least admits to this. Woodworkers pursue the craft because they love it. They enjoy working with wood, and they get great satisfaction from seeing a well-finished piece. They try their hardest to do fine work and to produce an artifact of delight. I don’t suppose there has ever been a time when so much effort has gone into producing good work.

Since the last great war, it seems that these same principles have been adopted by modern woodworkers. Yet the motivation is entirely different. I have never known a craft woodworker who does the job only for money, or at least admits to this. Woodworkers pursue the craft because they love it. They enjoy working with wood, and they get great satisfaction from seeing a well-finished piece. They try their hardest to do fine work and to produce an artifact of delight. I don’t suppose there has ever been a time when so much effort has gone into producing good work.

Unfortunately, a large part of the works on show are made by machines. And at what cost! Many thousands of dollars are spent on these machines, saws and re-saws, lathes, planers, thicknessers, spindle molders, mortising machines, doweling machines and biscuit joiners, dovetail attachments, belt sanders and portable machines of all kinds. New ones every week. Apart from the initial expense of this armory, there are attachments to buy, numerous cutters for different profiles and sawblades to be bought. Few of these things can be satisfactorily sharpened by the user. They have to be sent away. The operator becomes a mechanic producing precision engineered works. This has little to do with woodworking.

What about the extra time it takes to do a piece by hand? Well, it can take a little longer, that’s true. You need to be well organized, the workshop needs to be laid out properly and, above all, you must have a first-class bench. You must know your tools. Everything must be clean and sharp. Tools talk to the craftsman. You will know when they are right. What the machine does by noisy, brute force you will be able to do with quiet cunning.

I doubt there’s much of a saving in machine work over hand work for the small, one-off maker. If you’re an amateur, it doesn’t matter, and the quality will be so much better. A professional will have to charge a little more. People will pay it. With the saving in capital cost, bank interest and the time-consuming business of setting up machines, you could be better off anyway.

It is difficult to know whether machine-mania was led by the woodworking press or the craftsman. I am inclined to the former opinion. It looks as though the machinery manufacturers have the technical press in a vise-like grip, leaving the humble hobbyist to believe that unless he buys the machines, he will be a second-class woodworking citizen. I was always led to understand that machines were there to do the tedious work and that the craftsman’s skills should actually do the making. Gradually, the idea of what is tedious has been updated, for it is now possible to make complicated pieces entirely with machinery. The only handwork left to be done is to lift the wood to the machine. I am sure the manufacturers will cope with this in time!

From Fine Woodworking #127

From Fine Woodworking #127

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below:

Comments

Great article, but to bed devils advocate, I years ago tried the same path, but these were my barriers which sent me back to power.

1. Cost of hand tools to do same job as machine, for example , to buy a Stanley multi plane, plough plane, moulding planes etc etc, was more than a good router and bits.

2. As an amateur I had no knowledge or teaching in how to sharpen blades unlike an apprentice in carpentry would have.

3.No matter how hard I tried, jointing boards by hand to make a table or cabinet top just didn’t work, always gaps and if I did manage to get there the top ended up smaller than my design. Using a helical head combo machine I can get results every time and with minimal waste, as we know, more so down here in Oz, timber is at a premium.

I acknowledge the hand skills and tools are an art, I still read my bibles by Roy Underhill.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in