In 1970 I was in the furniture design program at Sheridan College outside of Toronto, Canada. The program was set up to train designers for the furniture manufacturing industry in Canada. A steady stream of young, well-known ambitious designers made up the rotating part-time staff. A constant was an elderly Italian born technician who oversaw the workshop and the often half-crazed students attempting to fabricate prototype ideas for the various product design assignments. Even as a 19-year-old first year student I could see Bruno Armellin possessed a calm attitude amid the chaos that could only come from the fact he had confidence in his abilities to solve any fabrication challenge that came his way. Bruno helped set up this program in the days of unlimited spending on colleges. His workshop had the latest in European woodworking equipment with one exception, a well-used Rockwell 20-in. bandsaw. He often spoke of its simplicity and versatility.

While attempting to get my sketchy ideas into three dimensions I would watch Bruno calmly look at what I had in mind. He would reach behind a machine to a variety of carefully made and labeled jigs that hung on the wall. If nothing suited the purpose he would fabricate a jig on the spot. I watched him draw lines, curved or straight, and with incredible precision cut right to the pencil line freehand using the old bandsaw.

There was something special happening there and I wanted to know more. I started having lunch with Bruno and over the three years learned of his journey from Italy in 1938 when he was conscripted into the Italian army and sent to Ethiopia. The Italian garrison was captured by the British early in the war and he spent the balance in a prisoner of war camp. Being a former apprentice furniture maker he made the furniture for both the British and Italian officers. Without his tools he made what he needed from bits of metal found around the camp. One lunch time he brought out a box of tools, drawings, and books that I will remember for as long as I live. It contained a collection of exquisitely made chisels, planes, and measuring tools. Bruno eventually emigrated to Canada and began working for an exceptional furniture company in Toronto where he was prized for making specialized production jigs. The story of Bruno’s life that brought him to the design school unfolded for me over many awe inspiring lunches.

At about the same time one of the design instructors, Chris Sorensen, encouraged me to apply for a scholarship to work and travel throughout Europe. This was of course before the internet and dozens of letters, actually a few hundred, were sent out trying find opportunities. Alan Peters, one of the few that responded, requested a portfolio and I was engaged for three months as an intern for Alan in his idyllic workshop in Devon, England.

In contrast to my school experience, Alan had marginal stationary woodworking equipment, some might have easily been Boer War vintage. I found all were cranky and intimidating to say the least. After rearranging tons of wood I was allowed to participate in a project. I was to make a sold wood chess board by insetting holly wood squares in African paldao.

I looked for the router and straight edges only to be told it would be done by hand. Alan in his calm way nudged me aside and proceeded to efficiently scribe the lines and chisel out the cavities with amazing speed and precision. We worked on bookcases for the high courts in London England again in paldao, this time it was curly. Joinery was dadoes cut with a handsaw, waste removed with a hand router, and dowels bored with a brace and bit. Miles of beading was done with a shopmade scratch stock. The scratch stock tamed the curly grain while even my limited woodworking knowledge knew a router would leave a chipped out mess. Life-long lesson learned.

My “design for production” education and the importance of learning hand skills has influenced how I design and make my own furniture every day. I always look for the best way without any bias.

Those experiences created a workable balance that has allowed me to make a living for almost 50 years and be deeply appreciative of every single minute in my workshop.

The first years as a furniture maker were slim. Part way through Taunton Press began publishing Fine Woodworking magazine in 1975. At the time there were only a few books of any use and even fewer people in my area to learn from. Here now was a source of information that was current and presented in a clear and relevant way. And it showed me that there was a whole community of woodworkers across North America that was just as keen to learn furniture making as I was. To become a contributing editor to Fine Woodworking has truly been an honor to share what I have learned along the way.

Michael Fortune

Contributing Editor, Fine Woodworking

|

Flawless Curves on a BandsawTricks and tips for surprisingly smooth cuts by Michael Fortune |

|

Tapered Laminations Made EasyA single jig tapers the plies on the bandsaw and then guides them through the planer by Michael Fortune |

|

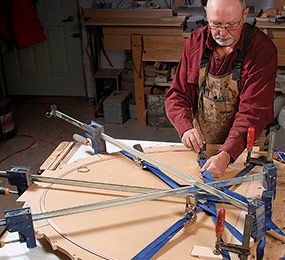

How to Tame Tricky Glue-UpsSome thoughts on working wood by James Krenov |

|

Strong and Handsome: Half-Blind Mitered DovetailsRouter jig simplifies a challenging joint by Michael Fortune |

|

This Stand Really DeliversAdjustable work support is a versatile, sturdy shop helper by Michael Fortune |

Comments

I follow Mr. Fortune and have always been quite impressed with his depth of knowledge and readiness to share it with those of us with less time in the trade/hobby. Thank you kindly, fine sir, for your good heart.

i made the roller stand a while back. i use it daily with my table saw and with my band saw especially when i am resewing. it works great. but, anything MF suggests making works great.

when i move to my new shop next year i plan to make another

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in