Synopsis: Jere Osgood says the key to the compound-staved lamination system is realizing that flat layers of wood can be bent to one radius at one edge, and to a different radius at the opposite edge. When he wants a slightly convex stave, his trick is to resaw and plane the lamination stock, allowing the pieces to dry a bit concave. He marks the convex face of each laminate, and when gluing up the stave, he stacks all the convex cups in one direction. He explains how to handle plain, straight-grained wood and highly figured wood, and he includes sketches of projects he’s undertaken with gentle curves. There’s information on how to make these projects yourself, along with tips on bandsawing the form ribs and understanding the angles involved in projects like these.

From Fine Woodworking #17

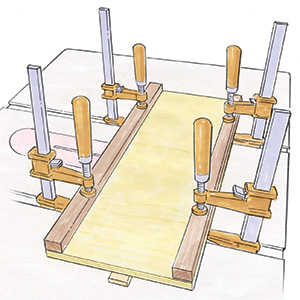

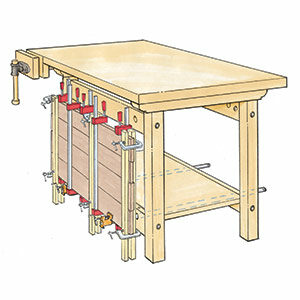

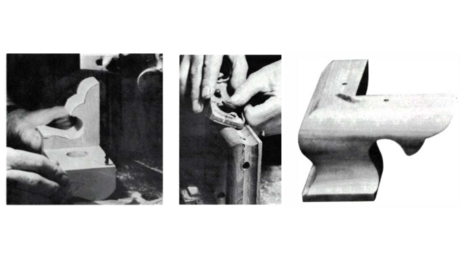

Thin layers of wood are easy to bend into a variety of simple curves—that is, surfaces that bend in only one plane. The basic techniques of layout, stock preparation, making press forms and gluing up are described in my earlier Fine Woodworking articles (“Bent Laminations,” Spring ’77 and “Tapered Laminations,” January ’78). The same approach can be used to create thin-walled panels that curve in two planes, for use as cabinet fronts, doors or sides, for drawer fronts, or for any other application requiring a compound-curved form. It is done by gluing layers of wood face to face into relatively narrow staves, making each stave take the shape of a different but related curve, and then joining the staves edge to edge. The key to the compound-staved lamination system is realizing that flat layers of wood can be bent to one radius at one edge, and to a different radius at the opposite edge.

Keep in mind that the surface of each stave is a portion of the surface of a cone, straight across its width. A single stave cannot take the shape of a section of a sphere or of any other surface that curves in two directions. Wood is not normally elastic and it will bend in only one plane at a time. However, a number of staves, each bent to a different radius, can be edge-joined together to produce an approximately spherical form (like a barrel or even a pumpkin) or almost any other three-dimensional surface. This assembly will be made up of a number of flats, like the outside of a barrel, but as long as the radius of curvature is not too sharp and the outer laminate is thick enough, you can plane, spokeshave, scrape and sand the surface to a smooth, continuous curve.

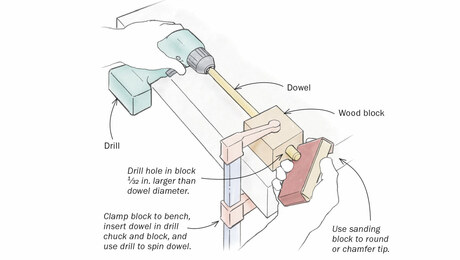

When I want a slightly convex stave, there is a little trick that is helpful, although fallible. I resaw and plane the lamination stock and sticker it overnight. The thin layers usually cup slightly as the moisture gradient within the original board reaches atmospheric equilibrium. I then mark the convex face of each laminate, and when gluing up the stave I stack all the convex cups in one direction. When the press form is opened after the usual glue-curing period, the stave will be perfectly flat across its width. But within 24 hours it usually resumes the cup.

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in